Another work which stands on the edge between Dalí's periods of Surrealism and Classicism. This painting is also very important for several other reasons, namely that it was the very first work to be purchased by Mr. and Mrs. A. Reynolds Morse, the renowned collectors of Dalí's art who founded the Salvador Dalí Museum, in St. Petersburg, Florida. When the Morses saw the painting at auction, they decided to purchase it, and felt that they had gotten quite a bargain. However, when they went to purchase the painting, they found that Dalí refused to sell the work without the original frame along with it. Apparently, Mr. Morse had only purchased the work itself, and actually had to pay more for the frame than for the painting! This anecdote is a good example of the way Dalí had matured, with Gala's help, into a shrewd businessman who was keenly aware of his value.

However, rather than being sour about the experience, which would have been understandable, the Morses instead started buying more and more works, and eventually became lifelong traveling companions and friends of the Dalí's. It was their efforts that gathered together nearly 100 oil paintings, hundreds of watercolors and drawings, and a vast archival library that now comprise the museum in St. Petersburg, Florida.

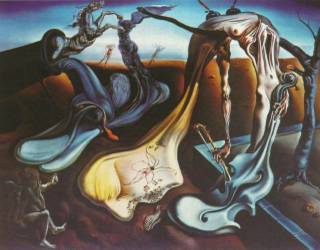

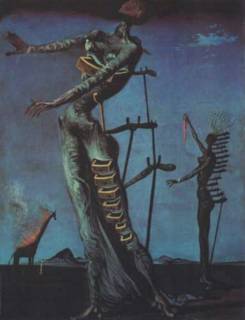

Each of the objects in the work itself is done in stunning detail. The scene is set upon an apocalyptic plain, and one immediately seems to get a feeling of dread or misgiving. Because Dalí intended this work to be an examination of the horrors of World War II that had now begun in earnest, Dalí fills the scene with allegorical references to that event.

In the upper left hand corner of the painting stands a cannon, propped up by a crutch which here symbolizes death and war. Out of the mouth of the cannon spill two distinct objects, the lower being a 'soft' or somewhat fluid biplane, and the other a white horse, galloping at a mad pace, its muscles and facial contortions suggesting power, speed and control.

The horse may symbolize one of the Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse, and the events of 1940 in Europe could have certainly appeared Apocalyptical, especially to one as sensitive as Dalí. The soft airplane, and another nearby object, the winged victory figure, are symbolic of "victory born of a broken wing" as Dalí described it. Salvador felt that the use of air power would be the decisive element of the war, the very key to victory itself. History has shown that this is at least partially true.

Nearer the center of the painting is another soft figure, what Dalí calls a 'soft self-portrait', an image from other works long since past. Its decaying body is drooped over a dead tree, it has two inkwells propped on it, and it's holding a violin. The ink wells are symbolic of the signing of treaties, although Dalí also occasionally used them to express sexuality as well. There are ants quickly devouring the soft head, and though we have not seen very many Dalínian ants to this point, they are another common symbol for Dalí. In general they represent decay and decomposition, as it is they (and many other insects as Dalí might point out) who eventually devour everything in the ground, and return it to its chemical components. For this reason Dalí often included ants as symbols of death, decay, and purification, all of which he was obsessed with.

In the lower left hand corner, a cupid figure looks on the scene, holding its face in one hand, and reaching out the other towards the destruction he sees before him. This agonized cupid almost seems to verbalize its horror in overlooking the terrible scene being played out before it. Remember that Dada, and eventually Surrealism were born out of the rebellion against the mindless destruction of World War I. In reality, none of the issues that caused that war were ever rectified, and this led to World War II, which shocked and outraged Dalí and many others, prompting these sorts of works that seem to say "Dear God not again!"

However, in the midst of such pain and terror, there is always hope, and this is symbolized by the daddy longlegs spider resting in almost the exact center of the painting, near the ants on the soft self portrait. The daddy longlegs, when seen in the evening, is a French symbol for hope. Thus, Dalí is offering us solace, even in the middle of such terrible devastation. This dualistic nature of his is slowly starting to shift more and more towards the positive, and towards themes and subjects that are more in the conscious realm of things. This predates his entering his Classical period in 1941, but shows the same tendencies nonetheless.